Understanding the Impact of Rural and Agricultural Finance

HOW WOULD FARMERS MEASURE THE IMPACT OF FINANCIAL SOLUTIONS?

Employing a human-centered design methodology, DIG worked with the Rural and Agricultural Finance Learning Lab to analyze the impact of rural and agricultural finance in Ghana and Kenya from the perspective of smallholder farmers, and inform future approaches to measuring impact. Learn more about the Master Card Foundation Rural and Agricultural Finance Lab.

Understanding the Impact of Rural and Agricultural Finance

HOW WOULD FARMERS MEASURE THE IMPACT OF FINANCIAL SOLUTIONS?

Employing a human-centered design methodology, DIG worked with the Rural and Agricultural Finance Learning Lab to analyze the impact of rural and agricultural finance in Ghana and Kenya from the perspective of smallholder farmers, and inform future approaches to measuring impact. Learn more about the Master Card Foundation Rural and Agricultural Finance Lab.

APPROACH

We were not asking the farmers to provide outcome data so we could measure impact on predefined indicators. Rather we wanted to know how they would describe impact in the first place, i.e., what impact indicators were most important to them. Each conversation took place on the interviewee’s farm and lasted about two hours, covering topics ranging from farmers’ daily activities to their use of financial instruments to their aspirations. The results of this field work are excerpted from the broader study here, along with images and direct quotes from the farmers.

Read about the primary Learnings from our research

Review our Practical Recommendations to increase impact

For more information, visit: Rural and Agricultural Finance Learning Lab and download the PDF version of this report

The Dalberg team undertook in-depth interviews with 28 farmers in Ghana and Kenya. This is of course not meant to be a representative sample, but rather to provide a source of qualitative insights. Two of the Learning Lab’s partner organizations—Opportunity International and One Acre Fund— supported the team in choosing a diverse group of clients to interview; the team also conducted interviews with a group of farmers not affiliated with the partner organizations.

The objective of these interviews was to understand and capture farmer perspectives on success in order to inform future approaches to measuring impact. The study covers questions such as: What is the theoretical framework for impact? How would farmers define impact?

What does the current evidence suggest? What are practitioners doing today to measure impact? How can we address current evidence gaps?

I previously brewed beer but switched to growing cocoa because it was a more stable income source for me as the sole bread winner of my family. I can now invest in my children’s education, one of whom is about to join nursing school. I wish I had initially invested more in farming as I would have had higher returns now.

- Faustina

statement_1

statement_1

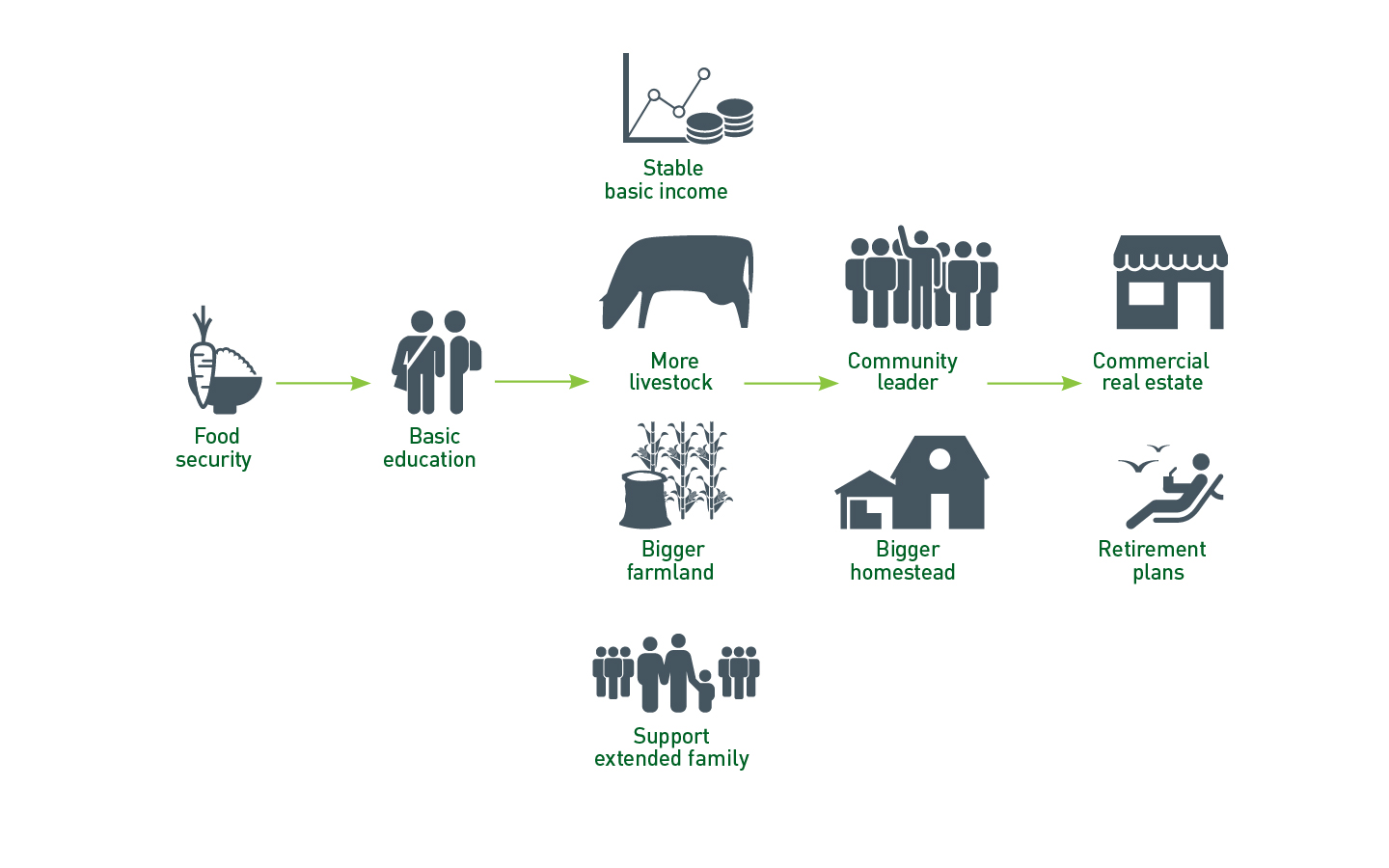

The farmers interviewed had a very clear prioritization of end goals, typically starting with meeting an essential need, such as putting enough food on the table, before progressing through a series of steps perceived as representing increased success. The figure below shows how a smallholder finance client might start out at a certain point along an axis of priorities and his/her priorities evolve over time.

statement_2

statement_2

Once they succeed in providing these basics for their families, the farmers see impact in their lives as expanding their farms, supporting extended family and their broader community, and later, making investments for retirement.

Farmers interviewed in Kenya were typically noncommercial smallholders and more focused on subsistence. Their most important priorities – and thus desired financial solution outcomes – were meeting basic needs such as food security and secondary needs such as rudimentary education for children, as demonstrated in the graphic below.

statement_3

statement_3

While geographical factors play a role, we believe that the primary driver of the difference in priorities cited by interviewees in Kenya and Ghana stems from a farmer’s stage in farming rather than his/her location. Even though the differing profiles of farmers interviewed in Kenya and Ghana led them to measure success differently, we anticipate that measures of success would converge to some degree across the two countries if the farmer stage were similar.

Farmers interviewed in Ghana had a stronger commercial focus—typically dedicating at least a portion of their farm to cash crop production—and prioritized increasing their production and income as demonstrated in the graphic below. Once that was achieved, impact looked like investing in their homes (moving from a rental or shared situation to their own property) and farms, as well as in their children’s advanced and/or private education. Eventually, they could consider diversifying their income sources through other kinds of farming.

Understanding the priorities of farmers is important not just for the design of financial solutions but also for the measurement of impact.

By understanding where a particular customer is along the curve of household needs or outcome priorities, finance providers or researchers can design more effective evaluations of impact. First, this baseline will better enable providers to understand what success looks like from the client’s perspective and to assess the degree to which they are helping a client achieve these goals. Second, this knowledge can improve the accuracy of impact assessment efforts. If research measures an outcome that the household is not prioritizing – for example cash profits for a household prioritizing food security – it may be less likely to find a statistically significant result, and could understate the impact of an intervention.

Education is important for my children as they will grow to have the innovative thinking that will allow them to emerge as better farmers and business people than I currently am

- Godfrey

This human-centered approach is a participatory evaluation methodology, which can make research designs more relevant.

In participatory evaluation, a broader set of stakeholders actively participates in developing and implementing the evaluation. This means that RAF funders, providers and clients all play a part in a process that incorporates opinions of the farmer/client in both evaluation design and execution. Our study did not comprise a full evaluation, but our team spent two weeks immersed in rural Kenya and Ghana so that farmers could influence the framing of the study by providing a nuanced view of their priorities and how financial solutions assist them in achieving these objectives.

We identified a diversified sample of target interviewees based on characteristics such as gender, age, experience with financial solutions, type of crop farmed, etc. Then we conducted a lengthy on-farm interview, learning about the farmer’s family, daily activities, experiences with financial products, and hopes and aspirations.

“I plant several varieties of maize and continue to advise my fellow farmers on what the best seeds are to use in their farms. I have also organized a number of farm visits to my farm for other farmers to come and learn.”

- Fredrick

The degree of comfort cultivated by being embedded in the farmers’ setting allowed for greater depth and honesty in sharing experiences.

Being comfortable, farmers shared a wide array of insights into their lives and circumstances. Capturing multiple dimensions of the farmer lent additional nuance to how we think about measuring impact. For instance, while many impact studies prioritize income measurement, it was clear that for the farmers interviewed in Kenya, paying school fees was much more important—and this could be done through bartering. Focusing on standard income measures would likely miss a high-priority outcome: an increased ability to cover school fees. Another key benefit of this process was the sense of reward that farmers felt in contributing to the solution generation process.

“My future ambition is to start a business. I am however worried about taking a cash loan without a clear business plan”

- Peter

practical recommendations

practical recommendations

1. Speak to a diverse sample within the target client segment:

To gather a wider set of qualitative insights, the team looked to identify farmers representing varied profiles, which would include a balance in gender, geographic location, and type and stage of farming. (Providers may want to seek diversity within the bounds of a clearly defined target segment.) To achieve this, the team (i) worked with partner organizations on the ground to recruit farmers based on pre-established criteria and (ii) independently recruited farmers through local leaders and at local markets.

2. Utilize local experts:

We were aware that a team conducting interviews in a foreign country could encounter cultural barriers arising from differing social norms. To moderate this, the team (i) interviewed experts on the ground (e.g., field officers) to better understand local norms, and (ii) worked with translators to ensure that they had sufficient training to ask accurate questions and do so in a way that was sensitive to farmers.

3. Mitigate external influence on the participant’s narrative:

It was important to allow interviewees to articulate their views with honesty and transparency, in order for the participatory approach to be successful. The potential existed for community leaders or partner organizations to influence the process through making the farmer introduction (i.e., the farmer might have felt an implied expectation to respond in certain ways) or through their presence at meetings; as external evaluators we worked to temper this influence by: (i) communicating with farmers directly once given their contact information, (ii) conducting the interview without a local leader or partner organization staff present, (iii) spending the initial part of the conversation clarifying the purpose of the interview, and (iv) providing opportunities for the farmers to be in the “position of power” in interviewsby allowing them to lead us, show us, take us around, and ask us questions.

4. Preserve transparency of the respondent’s voice:

The team should pay attention to factors that may distract farmers from presenting their views accurately, including their past experience interviewing, to ensure responses best reflect the farmers’ true circumstances. In addition, it is important to ensure that the form of media capture chosen does not distract from the purpose above. For example, if video recording is necessary but puts farmers on edge, the team can use an approach that includes writing key insights from the farmers during the interview and have the farmer repeat these into the camera at the end of the interview.

5. Revise approaches on an ongoing basis:

Working in the field requires flexibility to adapt the interview process and content based on emerging findings. A field team should have daily check-ins to gauge the relevance and sensitivity of questions in the interview guide (in terms of both context and tone). In addition, it is important to have review sessions with translators to ensure that their approach to asking questions is appropriate. Finally, the team should be flexible enough to recruit a wide range of respondents and change its recruiting approach based on what is emerging as effective.

CONCLUSION

Making time and space for clients to influence our log frames can surface new ideas for how to serve them better – the aspirations of our interviewees have clear implications for which financial solutions might be most effective. Listening to clients can reveal which outcomes we should measure, and which would be a waste of effort. Just as importantly, it puts us in the position to hear a story that could change the way we think about our work.

Defining impact and developing measurement frameworks often take place in a conference room at a hotel in the capital city, where no clients are present. We seem to know the impact we are trying to achieve without asking clients what they care about. While spending hours talking to individual farmers is time-consuming and does not always reveal earth-shattering insights, can we fully understand our impact if we don’t know how our clients would define success?